[ARTICLE] Drug-led Combination Products: Checklist to get a Notified Body Opinion

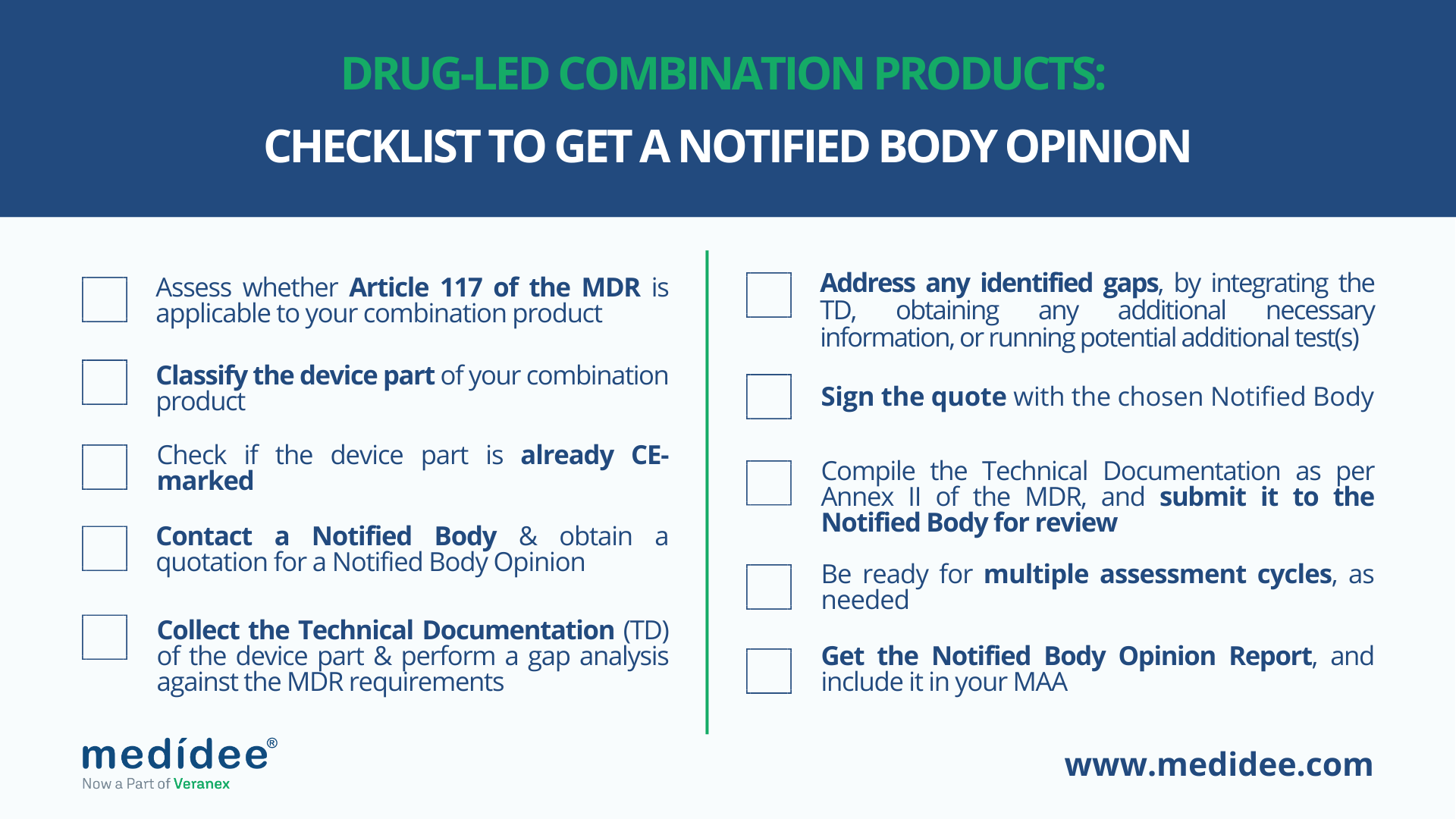

If you are a manufacturer of a drug-led combination product, you may need to include a Notified Body Opinion (NBO) in your Marketing Authorization Application (MAA). In the following paragraphs, you will find a step-by-step overview to find out whether this is applicable to you and, if so, how to achieve this important milestone in your product’s pathway to market.

1. Assess whether Article 117 of the MDR is applicable to your combination product.

Article 117 of the Medical Device Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (MDR) amends Annex I of Directive 2001/83/EC, point 12 of section 3.2, requiring to provide evidence of compliance with the General Safety and Performance Requirements (GSPRs) of the MDR for the device part of your Drug-Device Combination (DDC), when submitting your Marketing Authorization Application (MAA).

Article 117 of the MDR applies to Drug-Device Combinations (DDCs) that meet the following definitions, as defined in Article 1 (§8 and §9, respectively):

- DDCs incorporating, as an integral part, a medicinal product whose action is principal to that of the device; for example, a drug-eluting implant that slowly and locally releases the drug.

- DDCs intended to administer a medicinal product, which are placed on the market in such a way that the device and the medicinal product form a single integral product intended exclusively for use in the given combination and which is not reusable; for example, pre-filled syringes or transdermal patches

Therefore, if your product falls under either of these definitions, then refer to the steps below to find out how to comply with MDR requirements for the device part.

2. Classify the device part of your combination product

The MDR classifies medical devices into class I, Ir (“r” stands for “reusable”), Is (“s” stands for “sterile”), Im (“m” stands for “measuring function”), IIa, IIb and III, based on their intended purpose and related risks. In particular, Annex VIII of the MDR lists 22 rules, that should be assessed for applicability to the device part of your Drug-Device Combination: if multiple rules apply, the strictest rule resulting in the highest classification determines the class of the device part.

For example, according to Rule 20 of Annex VIII, inhalers are classified as class IIa, unless their mode of action has an essential impact on the efficacy and safety of the administered medicinal product or they are intended to treat life-threatening conditions, in which case they are classified as class IIb.

Of note, Annex VIII of the MDR should be read in combination with the MDCG guidance 2021-24 - “Guidance on classification of medical devices” to ensure the appropriate interpretation of the rules.

3. Check whether the device part is already CE marked.

There are three cases to be considered here:

a) If the device part is a class I (non-sterile, non-measuring and non-reusable surgical instrument) and is CE marked under MDR, include the Declaration of Conformity in the MAA, and ensure that the device is used within its intended use. No further steps are required.

b) If the device part is of any other class than I and is CE marked, include the EU certificate issued by the Notified Body in the MAA. No further steps are required.

c) If the device part is of any other class than I and is not CE marked, refer to the steps below.

4. Contact a Notified Body and obtain a quotation for a Notified Body Opinion (NBO).

You should select a Notified Body that is designated under the MDR and whose scope of technical competence covers devices as per Article 117. To find the Notified Bodies currently designated, please consult the NANDO (New Approach Notified and Designated Organisations) website.

5. Collect all the available Technical Documentation (TD) of the device part and perform a gap analysis against the requirements defined in Annex II of the MDR.

This includes, but is not limited to, design and manufacturing details, the risk management file and performed verification and validation activities (including their traceability). If the device is active, the electromagnetic compatibility and software development details should also be included.

6. Address any gap identified, by integrating the TD, coordinating with suppliers to obtain any additional necessary information, or running any potential additional test/s.

Medidee has a long track record of supporting medical device manufacturers with their Technical Documentation. We provide gap analysis services for multiple companies and help them succeed in addressing such gaps. Do not hesitate to contact us, should you feel that you would also benefit from our support.

7. Sign the quote with the chosen Notified Body.

8. Compile the Technical Documentation as per Annex II of the MDR, and submit it to the Notified Body for review.

9. Be ready for multiple assessment cycles, as needed.

Medidee has successfully supported clients in compiling the Technical Documentation, submitting it, and interacting with Notified Bodies. As questions are raised during the review process by the Notified Body, we help you address them in a timely and comprehensive manner.

10. Once all questions with the Notified Body are closed, the Notified Body will finalize and send you the Notified Body Opinion Report, for you to include in your MAA.

EMA and National Competent Authorities (NCAs) recommend submitting evidence of compliance with the GSPRs of the MDR for the device part of your combination product already in the initial MAA for the medicinal product to avoid additional clock stops.

As an example of timeframes to be considered for obtaining a NBO, TÜV SÜD has published on its website the required Application Form for Notified Body Opinion per Article 117, laying out the timelines of their examination process. According to their process, getting a non-binding quotation after submission of the Technical Documentation could take up to 2 months, and the review process may take 3 more months, depending on the questions raised.

Hence, at least 6 months should be accounted for obtaining the Notified Body Opinion once the Technical Documentation is ready. Early contact with a Notified Body and performing a gap analysis of the Technical Documentation of the device part against MDR requirements are critical steps necessary for you to draw the project timelines.

If this is something you are currently working on, do not hesitate to check our full offering of Combination Products Services, or to reach out directly for expert support.

This article was written by Bruno Strappa (MSc) and Rima Padovani (PhD, RAC).

[ARTICLE] Substance-based Products: Medicinal products, Medical devices or Cosmetics?

The qualification of a substance-based product as a medicinal product or a medical device can be challenging, with several products being “borderline”. In some cases, the product may even be qualified as a cosmetic product.

On the European regulatory landscape, this qualification is crucial in order to demonstrate compliance with the appropriate regulation: the Medicinal Product Directive (MPD, Directive 2001/83/EC), the Medical Device Regulation (MDR, Regulation 2017/745) or the Cosmetic Products Regulation (CPR, Regulation 1223/2009).

(Note: In some cases, the product may even be categorized as a biocidal product, in which case the Biocidal Product Regulation (BPR, Regulation 528/2012) applies, but for simplicity, this case is excluded from this article).

In this blog post, we provide an overview of the main aspects to take into consideration when classifying a substance-based product, to make sure you are following the right path from the beginning.

What is a substance-based product?

There is no official definition of a substance-based product. However, the definition of a substance is given in MPD, Directive 2001/83/EC.

Substance: "Any matter irrespective of origin which may be:

- human, e.g. human blood and human blood products;

- animal, e.g. micro-organisms, whole animals, parts of organs, animal secretions, toxins, extracts, blood products;

- vegetable, e.g. micro-organisms, plants, parts of plants, vegetable secretions, extracts;

- chemical, e.g. elements, naturally occurring chemical materials and chemical products obtained by chemical change or synthesis.”

This definition can be simplified into a ‘substance’ means a chemical element and its compounds, while being simple is not very descriptive.

For the purpose of this article, we will define a substance-based product as a product whose action is accomplished by its chemical constituents. These constituents may exist in the solid, liquid, or gas phase, and they may change from one phase to another during changes in temperature or pressure.

Examples of substance-based products include: eye drops, nasal sprays, hyaluronic acid gel for joint injection, among others.

Regulatory definitions

In Europe, Directives and Regulations apply to specific product categories, with the said products being defined in the regulations themselves. As introduced above, a substance-based product may be borderline between cosmetics, medicinal products and medical devices. The definitions of these three product categories are provided below.

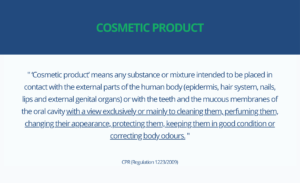

The CPR (Regulation 1223/2009) defines “cosmetic product” as:

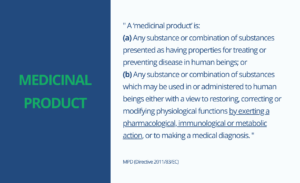

The MPD (Directive 2011/83/EC), in turn, provides the definition for “medicinal product”:

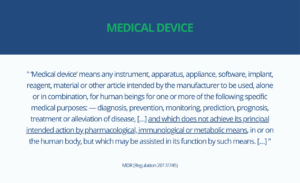

Finally, the MDR (Regulation 2017/745), defines what a medical device is:

Interpretation of the definitions

First of all, it is clear from the definitions above that a substance-based product may very well be classified as any of the three product categories above, because none of these definitions specifies the form under which a product acts or is used. The key parts of the definitions that can be used to distinguish the different products are underlined above.

Cosmetic Product or Medicinal/Medical?

The easiest distinction to make is between cosmetic products and medicinal or medical products. In this case, the distinction is made based on the intended use of the product. If the sole purpose of the product is to clean, perfume or affect the appearance of parts of the human body, without providing medical benefits, the product is qualified as a cosmetic product. In case the product bears a medical benefit (in fact, whether or not it is claimed by the manufacturer), the product would then fall either under the medicinal product directive or under the medical device regulation.

Medicinal Product or Medical Device?

Finally, making the distinction between a medicinal product and a medical device may not be straightforward in some cases because both products are then used for preventing, treating, etc. a medical condition. Here, the distinction between the two types of products is made based on the principal intended mode of action of the device. For products whose actions are accomplished by their chemical constituents (definition of a substance-based product), this means that the qualification of the product depends on the modes of action of its chemical constituents. To qualify such a product, it is therefore needed to evaluate whether the principal intended action of the product is achieved by a pharmacological, immunological or metabolic action. A substance with such mode of action is defined as an active substance by the MPD. Substances without such properties are deemed inactive.

In conclusion, whether or not the substance-based product (with a medical purpose) achieves its principal intended use by the action of an active substance determines the application of either the MPD or the MDR. Importantly, a product may have secondary (called ancillary) actions. In the case of a substance-based product, the most probable case is that of a medical device incorporating an active substance. Thus, the product is regulated as a medical device and General Safety and Performance Requirements specific to the active substance (as laid down in Annex I of the MDR) are applicable.

Navigating through the definitions and providing the required scientifically-sound rationales for qualifying substance-based products is of prime importance because it may dramatically impact the regulatory pathway (and burden) for market access.

Other specific cases

Herbal products

Herbal medicinal products are considered active ingredients (Article 1 (30) of the MPD), however, historically, for traditional herbal medicinal products, the mechanism of action did not need to be described. Such products were approved for sale based on plausible pharmacological effects or efficacy due to longstanding use and experience.

Importantly, if the manufacturer demonstrates that the product’s mode of action is not pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic, these products might qualify as medical devices under the MDR. With that, the MDR provides the possibility for such products which were considered complementary and alternative medicine, to qualify as medical devices within an evidence-based framework.

How Medidee can help

At Medidee, our expertise includes the support to qualify and classify your substance-based product by reviewing the scientific literature and writing the required classification justification. Medidee also has the experience to provide the necessary documents for fulfilling the additional requirements for substance-based medical devices.

This article was written by Dr Cornelia List and Dr Adrien Marchand.

[ARTICLE] In-Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Q&A: State of the Art in IVDR

As required by the IVD Medical Device Regulation (EU) 2017/747, a device performance evaluation plan must contain a description of the state of the art pertaining to the IVD device under evaluation.

All relevant aspects related to the evaluation of the performance of a device must be weighed against the current state of the art. These include:

- the demonstration of scientific validity, device analytical performance and clinical performance;

- the evaluation of the risk control measures implemented;

- the technical safety of the device;

- the IVD’s expected clinical benefit.

In other words, the clinical evidence must be such as to scientifically demonstrate, by reference to the current state of the art of medicine, that the IVD medical device has a positive risk/benefit ratio. Cited 20 times in the IVDR (EU) 2017/747I, for example in relation to the design of in vitro diagnostic medical devices, as well as risk management, performance evaluation and post-market surveillance, it is clear that state-of-the-art assessment plays a central role in the overall life cycle of a device and not just in relation to performance evaluation.

In this blog post, we provide comprehensive answers to some of the most common questions about the state of the art in IVD medical devices.

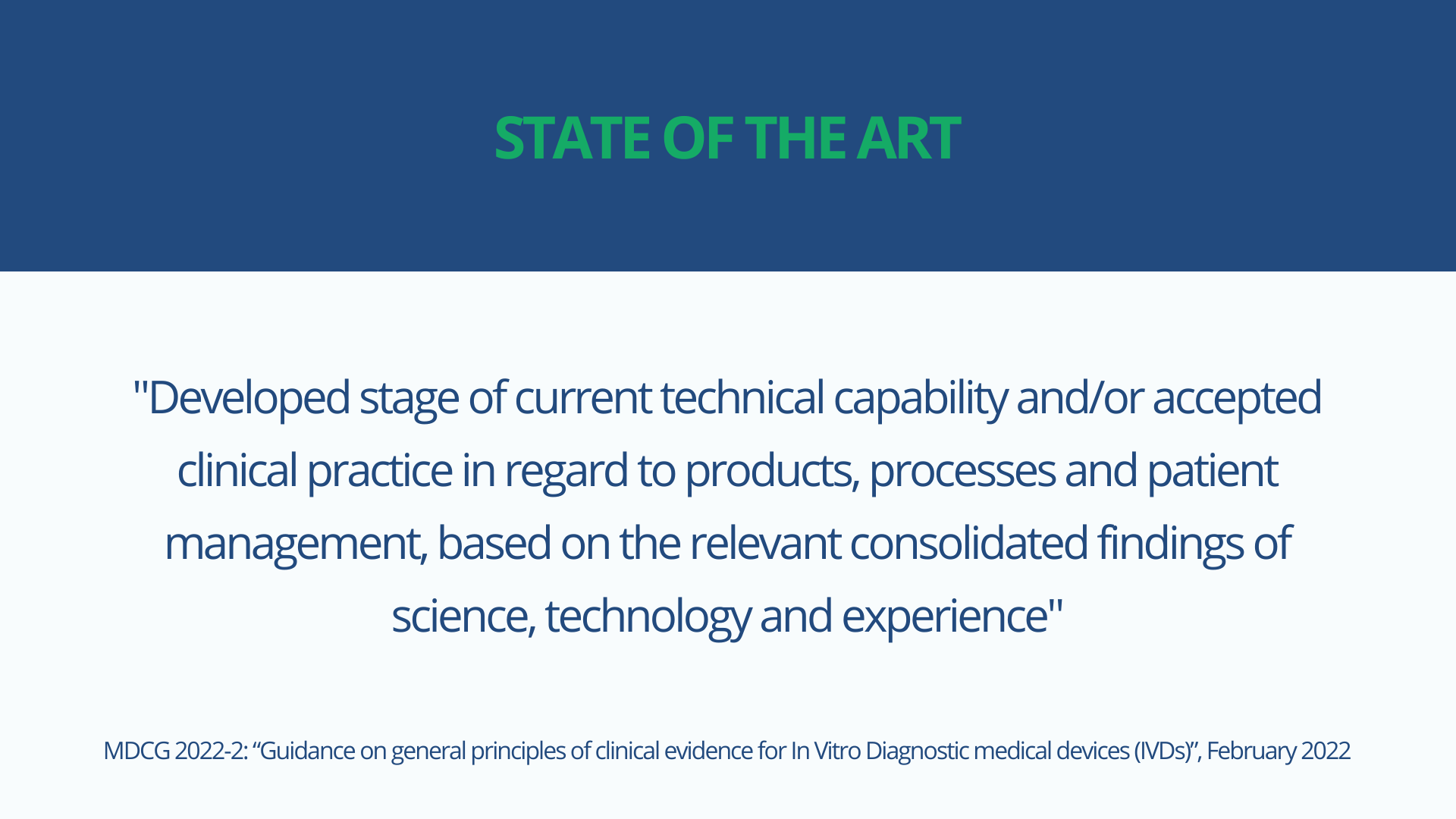

What does “State of the Art” mean?

Manufacturers are expected to regularly, throughout the device life cycle, review and evaluate the evolution of the state of the art for their IVD medical devices.

However, there is no formal definition of state of the art in the IVD regulations. MDCG 2022-2 published in February 2022 and entitled “Guidance on general principles of clinical evidence for In Vitro Diagnostic medical devices (IVDs)” defines state of the art as:

It further clarifies that the state of the art embodies what is currently and generally accepted as good practice in technology and medicine, which does not necessarily represent the most technologically advanced solution.

Therefore, state of the art should be understood as the accepted standard clinical practice in a particular medical field, which is not necessarily the most advanced technology, and should be used to demonstrate the acceptability of the IVD medical device based on that current knowledge.

As per IVDR requirements, the state-of-the-art description shall include the identification of existing relevant standards, CS, guidance or best practices documents. Furthermore, the state-of-the-art assessment may contain a mix of:

- what is currently considered best clinical practice for diagnosing/detecting or monitoring a particular condition/disease;

- what biomarkers are commonly accepted;

- what technology is most commonly used to measure those biomarkers.

As the state of the art evolves over time, such an evaluation must be conducted regularly to reflect the most recent knowledge.

To give a concrete example of the possible evolution of the state of the art over time: for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction, the creatine-kinase-MB assays were for years considered the standard of care. In the last 10 years, however, these assays have been replaced in routine clinical practice by assays measuring cardiac troponin and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin. However, the technology for detecting these biomarkers, namely immunoassays, remains the same.

When to start the assessment of the state of the art?

The findings of the state-of-the-art assessment will impact several parts of the device's technical documentation. First, the results of the state-of-the-art assessment may trigger design choices, such as using one particular technology over another or using a specific biomarker or set of biomarkers over others.

In addition, the risk control measures adopted by manufacturers for the design and manufacture of devices must be in line with safety principles, taking into account the generally accepted state of the art. The results of the state-of-the-art assessment will therefore also have an impact on risk assessment and management.

Furthermore, the "state of the art" is not only used to address the clinical evidence of the device, thus being part of the performance evaluation plan, but it is also used to address the safety and performance summary for Class C or Class D devices and is a key component of the post-market surveillance (PMS) requirements. State-of-the-art surveillance is considered a proactive PMS activity and must be covered in the PMS plan.

Therefore, a state-of-the-art assessment must be conducted very early during the development of the device and must be regularly reassessed and updated, when necessary, through the PMS activities and during the entire life cycle of the device. The design and risk/benefit ratio of the device should be considered in light of the results of the most recent state-of-the-art evaluation.

How should the state of the art be assessed?

The assessment of the state of the art involves a systematic and methodological approach to the literature review, which requires time and resources.

Acceptable inputs for assessing the state of the art for an IVD may include:

- Published common specifications such as those published for the assessment of the performance of SARA-CoV 2 assays and for other class D devices

- Standards used for the same or similar devices

- Clinical guidance documents and medical textbooks

- Best practices, as used in other devices of the same or similar type

- Expert consensus documents produced by professional medical associations

- Publications from regulatory authorities or additional information for similar other products

- Recommendations from medical or laboratory associations

- Comparison of the benefits and risks of the device under development with the benefits and risks of similar devices available on the market

- Peer-reviewed literature, such as review articles on relevant condition/disease managed by the device, biomarkers or device technology.

The assessment of the literature must be conducted using explicit and systematic data appraisal and collection. For IVD medical devices there are currently no specific guidance documents describing how such a methodological review of the literature needs to be conducted to achieve an adequate state-of-the-art assessment.

The guidance document MEDEV 2.7/1 rev 4 entitled "Clinical Evaluation: A Guide for Manufacturers and Notified Bodies under Directives 93/42/EEC and 90/385/EEC" provides standards of good practice for methodological literature reviews, offering general instructions on literature searching and describing methods for developing a protocol for conducting a literature review.

Although this guidance document does not address in vitro diagnostic devices per se, it nevertheless represents the gold standard for methodologically reviewing the state of the art and can be used by manufacturers of in vitro diagnostic devices for this purpose.

It is important that manufacturers document the databases used for the literature search, as well as the applied search strings and keywords, and that identified articles are appraised using traceable and systematic inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the assessment of the state of the art is essential because it is needed to confirm the clinical benefit of the device, to justify the positive risk/benefit ratio of the IVD, and also to guide design choices and risk mitigation.

State-of-the-art evaluation is a living concept, which means that it must be evaluated throughout the life cycle of the device, with the clinical benefit of the device always being updated in light of the most recent state-of-the-art evaluation.

Most manufacturers are aware of the latest state of the art regarding their IVDs, but this is not always documented in a systematic and methodological way in the device's technical documentation. This can lead to unnecessary delays and an additional burden on resources when the device undergoes conformity assessment by a Notified Body.

It is therefore recommended that a methodological assessment of the state of the art be performed and documented early in the life cycle of the device and updated regularly to reflect the latest knowledge in the relevant medical field.

How Medidee can help

Medidee’s IVDR experts collaborate with your team to design and implement a strategy that is tailored to your specific challenges and needs, for a well-managed transition to IVDR.

Contact us to get started now!

This article was written by Dr Silvia Anghel and Dr Julianne Bobela.

[ARTICLE] International Market Access Strategy for Electrical Medical Devices and IVDs: National Differences and the Added Value of "CB Scheme" and "NRTL Listing Report"

This blog article focuses on the international market access strategy for medical electrical equipment, notably electrical medical devices including in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDs) and explains the relevance and benefits of establishing an IEC 60601 or IEC 61010 test report and certificate, following the CB (Certification Body) scheme test procedure, and respecting the national differences. In addition, the purpose of NRTL (Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory) listing report along with its requirements and benefits are summarized.

Manufacturers of electrically-driven medical devices and IVDs may face different regulatory requirements depending on the intended device market strategy. Due consideration of the applicable international market requirements during and after the development phase of the medical electrical equipment is therefore essential.

As part of the global market access strategy for medical electrical equipment, medical device and IVD manufacturers must comply with the “State-of-the-Art” (SOTA) concept. This is normally achieved through the application of relevant harmonized standards within the European Union, or of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognized standards for the United States of America, taking into consideration the device classification and intended use of the device/system.

General Considerations on International Market Access for Medical Electrical Devices and IVDs

First of all, medical device manufacturers should begin by determining the target countries in which they intend to place their medical devices on the market. Based on the country, it should be assessed if any national differences are applicable. Identified national differences should be considered early during the development of the medical device. This approach, known as “frontloading”, can enable substantial cost savings compared to conducting this process at an advanced development stage.

For instance, IEC 60601-1:2005+AMD1:2012+AMD2:2020 (3.2 Edition) and IEC 61010-1:2010+AMD1:2016 (3.1 Edition) contain a variety of national differences in applicable regulatory requirements.

Notably, the following country-specific IEC 60601-1 versions are applicable depending on the target country and type of medical electrical equipment at stake:

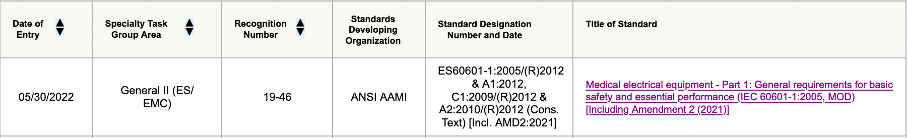

- ANSI/AAMI ES60601-1:2005/A2:2021 (United States)

- CAN/CSA-C22.2 NO.60601-1:14 (Canada)

- SI 60601 Part 1 (Israel)

- JIS T 0601-1:2017 (Japan)

- MFDS No. 2020-12 (Republic of Korea)

- BS EN 60601:2006 A1 (United Kingdom)

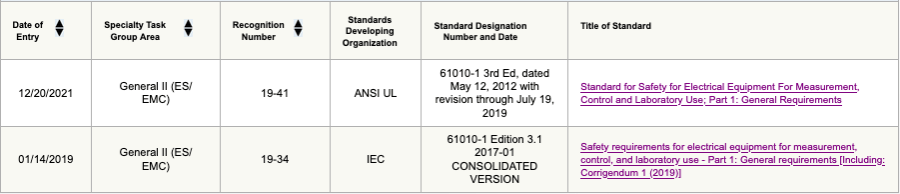

The following country-specific differences of IEC 61010-1 are applicable depending on the target country and type of in vitro diagnostic:

- CAN/CSA-C22.2 NO.61010-1+Amd1 (Canada)

- EN 61010-1:2010/A1:2019 (CENELEC)

- UL 61010-1 (3rd) AM.1 (United States)

The identified applicable national differences based on the target markets should be considered during the development and testing (verification) of electrical medical devices and IVDs.

It is important to note that FDA only recognizes the ANSI AAMI ES60601-1 standard, meaning that if the medical electrical equipment manufacturer plans to obtain market approval/clearance in the USA, they need to comply with the national differences for the USA presented therein.

Figure 1: Screenshot of ANSI AAMI ES60601-1 of FDA-recognized standard database

Furthermore, manufacturers should bear in mind that ANSI AAMI ES60601-1 3.1 Edition will be superseded by 3.2 Edition by 17 December 2023 according to the information provided by FDA, and therefore that after that date FDA will only accept submissions complying with 3.2 Edition.

With regard to the 61010-1 standard, the FDA recognizes the ANSI UL 61010-1 3rd Edition and IEC 61010-1 Edition 3.1.

Figure 2: Screenshot of ANSI UL/ IEC 61010-1 of FDA-recognized standard database

In a second step, medical device and IVD manufacturers should contact an external test laboratory to plan and conduct the required tests (e.g., as per IEC 60601-1 or IEC 61010-1) in accordance with the identified applicable national differences.

As an example – Canadian national difference (CAN/CSA-C22.2 No. 60601-1:14) requires, as stated in clause 8.6.4 “impedance and current-carrying capability”, compliance to CSA C22.2 No. 04. This implies a protective earth test current for cord-connected equipment of twice the rating of the attachment plug cap, or for permanently installed equipment, of twice the rating of the fuse for branch circuit, but not less than 40 A for 120 seconds.

In contrast, IEC 60601-1 3.2 Edition requires, according to clause 8.6.4 “impedance and current-carrying capability”, a protective earth test current of 25 A or 1.5 times the highest rated current of the relevant circuit for a maximum time of 10 seconds.

The Canadian national difference requirement in the above example is therefore stricter than the IEC 60601-1 3.2 Edition requirement. Depending on whether the equipment is cord-connected or permanently installed, the extent of the required construction (protective earth wire diameter) and compliance testing could be impacted.

Finally, please note, IECEE covers 23 categories of electrical equipment and testing services. Therefore, the CB Scheme is not limited to electrical equipment for medical use. As an example, three additional categories of electrical equipment are listed below, which are often used/ tested in combination with electrical medical devices and IVDs:

- Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)

- Safety Transformers and similar equipment (SAFE)

- Information Technology Audio Video (ITAV)

If it is intended to gain market access internationally, it is recommended to follow the IECEE (IEC System of Conformity Assessment Schemes for Electrotechnical Equipment and Components) CB (Certification Body) scheme of test procedure which facilitates the global market access.

What is the “CB scheme”?

The CB scheme is an international system for mutual acceptance of test reports and test certificates. Currently, 54 countries are member bodies taking part in CB scheme approach. Only certification body testing laboratories (CBTL) may issue CB test reports and certificates. All CBTLs can be viewed here.

Typically, the first page of an IEC 60601/ IEC 61010 test report indicates the test specification and the applied test procedure.

Figure 3: Example of IEC 60601 test report test specification

What are the implications for electrical (IVD) medical device manufacturers?

The CB scheme follows predefined requirements, and the medical device manufacturer and the external test laboratories are obliged to comply with specific rules, operational documents, and guidance.

For instance, the IECEE Operational Document OD-2055 Annex D requires IEC 60601-1:2005+A1:2012+A2:2020 compliance, in addition to a test report documenting compliance of usability in accordance with IEC 60601-1-6:2010+A1:2013+A2:2020. Any other applicable collateral standard (e.g., IEC 60601-1-3) shall also be considered.

Moreover, it must be noted that following the CB scheme does incur additional costs due to the additional requirements and certification fees (certificate) implied.

Last, it is important to know that according to clause 6.2.1 of IECEE OD-2020, only three amendment reports due to technical changes are accepted to the original issued test report and test certificate. After three amendments a new CB test report and certificate need to be requested and issued by the external test laboratory. Even upgrading the CB test certificate and report from an old edition to a newer edition of the standards requires a new CB test report and certificate.

Besides that, the CB scheme offers the following benefits to the medical device manufacturer:

- It enables fulfilment of the criteria for obtaining market access in certain countries – it provides direct acceptance by the regulatory authorities in many countries and is accepted by numerous retailers, buyers and vendors worldwide

- No additional duplicate testing is needed, and it is a globally approved and well-established procedure

- Simplification of the roll-over process (changing the external test laboratory)

- All CB certificates are listed in the IECEE database and are publicly accessible

Now, moving on to the NRTL listing report:

What is the “NRTL”?

Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory (NRTL) are mainly U.S.-based test laboratories recognized by the OSHA (Occupational Safety Health Administration) according to the Code of Federal Regulation (CFR) 21 §1910.7 to perform certification for certain products (e.g., medical electrical equipment or in vitro diagnostic) to ensure they meet the constructional and general industry OSHA standards. The NRTL will issue a separate listing report for the medical electrical equipment/ in vitro diagnostic manufacturer.

OSHA requires NRTL testing and affixture of the NRTL safety mark for electrical products used in public buildings or workplaces (e.g., hospital, clinics, and laboratories) in the United States. This is regulated by the National Electric Code (NEC) §90.7, §110.2, and §110.3 (C), and may be subject to control by Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJ) during the installation of the medical electrical equipment/ in vitro diagnostic or during operation.

What are the implications for electrical (IVD) medical device manufacturers?

- Electrical (IVD) medical device manufacturers require an external NRTL-recognized test laboratory. Currently, there are 21 listed NRTL-recognized laboratories

- The NRTL listing report and certificate need to be requested, incurring additional costs

- Initial factory inspection must be conducted by an NRTL inspector, and follow-up inspections at the factory site are needed every 3 or 6 months (additional initial and follow-up costs incurred)

- Manufacturers need to update the NRTL mark on the type label, and within the technical documentation such as in the instructions for use

The NRTL listing report puts focus on general constructional requirements (cable routing, labeling, protective earth connection, list of critical components) and routine tests for manufacturing and production (grounding continuity test, dielectric voltage withstand test, and leakage current test). These aspects will be regularly inspected during the ongoing factory inspections.

In addition, if it is also intended to obtain market access in Canada, it is strongly recommended to directly apply for an NRTL listing report for Canada in parallel. The NRTL listing report approach requested by the Standards Council of Canada (SCC) is similar to that for the U.S., and one combined NRTL listing report can be established for both countries.

Besides that, the NRTL listing report offers the following benefits to electrical (IVD) medical device manufacturers:

- It enables market access for the United States of America and Canada

- The electrical (IVD) medical device will bear the NRTL mark, showing that the NRTL tested and certified the product (quality property)

- Valid NRTL-certified medical electrical equipment, including electrical (IVD) medical devices, are listed in the related NRTL database

How can Medidee, now part of Veranex, support your company?

Our team of electrical safety specialists at Medidee can assist you in identifying the regulatory requirements, notably the applicable standards and national differences, for your target market(s). Moreover, Medidee can help you in determining if a test report according to the CB scheme and/ or NRTL listing report is mandatory in specific countries. In addition, we can support you in selecting the right external test laboratory depending on the intended global market access strategy and during the certification process and on factory inspection to ensure a smooth certification process of the medical electrical equipment or in vitro diagnostic.

Contact us to discuss your needs.

This article was written by Stefan Staltmayr and Dr Jérôme Randall.

[ARTICLE] Combination Products: Similarities and Differences of EU and US Regulations

The success of novel combination products is much dependent on the regulatory intelligence and foresight to define the best strategy to place and maintain them on the market, through a deep understanding of how drugs, devices and their combination are regulated in the different target markets.

This article aims to provide general guidelines for combination product manufacturers who may not be familiar with the EU and US regulations, or know one of these markets well and aim to access the other.

Terminology and definitions

The term “combination product”, commonly used to identify the category of medical products made of a combination of drug, device, and/or biologic, comes from the FDA definition given in 21 CFR 3.2 (e).

In the EU, instead, the wording “integral product” is used to refer to devices incorporating a medicinal substance (Article 1 §8), and devices intended to administer a medicinal product (Article 1 §9), as defined in the Medical Device Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (MDR). Of note, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has published a Q&A guidance document on this topic and the term “Drug Device Combination” (DDC) is also used.

In 21 CFR 3.2 (e), the FDA defines the following types of combination products:

- single-entity combination product in which its constituent parts are physically, chemically, or otherwise combined or mixed and produced, as a single entity;

- co-packaged combination product in which its constituent parts are packaged together in a single package or as a unit;

- cross-labeled combination product in which its constituent parts are packaged separately and, according to the investigational plan or proposed labeling, are intended for use together to achieve the intended use, indication, or effect.

According to the MDR, the same products are categorized differently, as follows:

- devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action ancillary to that of the device;

- devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action principal to that of the device;

- devices intended to administer a medicinal product, placed on the market as a single integral product (i.e. placed on the market in such a way that they form a single integral product which is intended exclusively for use in the given combination and which is not reusable);

- devices intended to administer a medicinal product, placed on the market as a “non-integral product”.

To provide some examples, a pre-filled syringe is a single-entity combination product in the US, and “a device intended to administer a medicinal product as a single integral product” in the EU.

A drug-eluting stent is a single-entity combination product in the US, and “a device incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action ancillary to that of the device” in the EU.

In the US, insulin cartridges to be used with a reusable pen injector can be a co-packaged combination product, if the insulin cartridges are provided in the same package with the reusable pen, or a cross-labeled combination product, if provided separately. In the EU, the reusable pen injector is “a device intended to administer a medicinal product as a non-integral product”.

Mode of Action to define how the product is regulated

Interestingly, the term “mode of action” is used both in the US and in the EU, but its definition is provided only in 21 CFR 3.2(k), which states that the “mode of action is the means by which a product achieves an intended therapeutic effect or action”.

Both in the US and in the EU, combination products are recognized to have more than one identifiable mode of action. Among the multiple modes of action, FDA defines as Primary Mode of Action (PMOA) “the single mode of action of a combination product that provides the most important therapeutic action of the combination product. The most important therapeutic action is the mode of action expected to make the greatest contribution to the overall intended therapeutic effects of the combination product.” (21 CFR 3.2(m)).

The MDR does not provide a definition, but rather distinguishes between “principal” and “ancillary” action of the medicinal substance to that of the device.

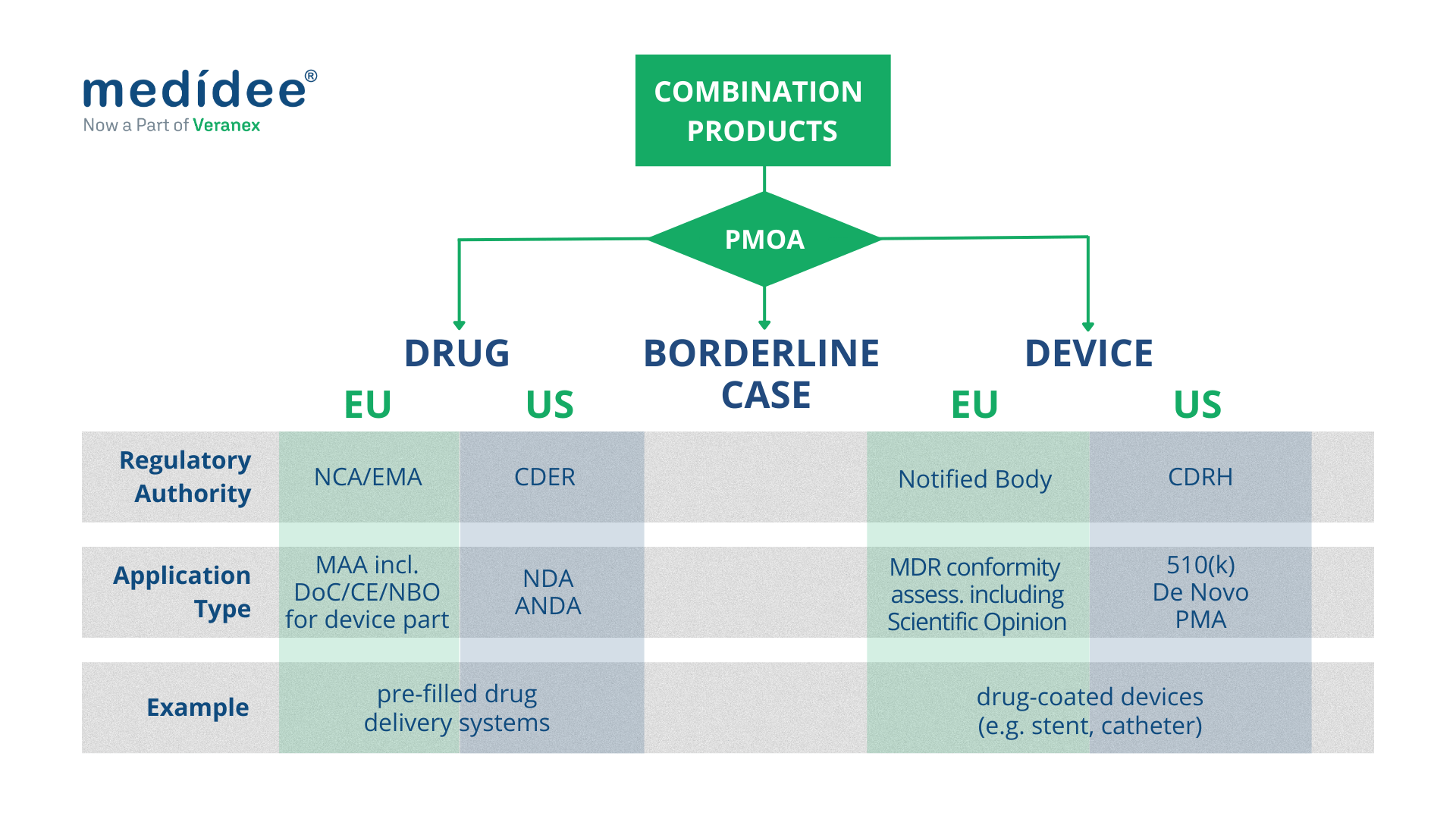

Finally, the “primary” or “principal” mode of action is the key criterion used in both US and EU's regulatory frameworks to define how the product is regulated and by which Regulatory Authority.

Combination Products regulated as medical devices

Both in the EU and in the US, combination products with a device PMOA, also called device-led combination products, are regulated as medical devices.

European Union

In the EU, this type of combination product includes “devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action ancillary to that of the device”, and “devices intended to administer a medicinal product, placed on the market as a non-integral product”. They undergo conformity assessment procedures as any other medical device, as defined in Article 52 and set out in Annex IX to XI of the MDR.

In terms of classification, “devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action ancillary to that of the device” are class III medical devices, according to Rule 14, as defined in Annex VIII of the MDR.

Instead, “devices intended to administer a medicinal product, placed on the market as a non-integral product” are classified differently depending on their intended purpose. Of note, the MDR up-classified some of these products: for example, inhalers were regulated under the Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC (MDD) as class I devices, whereas they are now class IIa or class IIb devices under the MDR.

Finally, as part of the conformity assessment procedure, “devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action ancillary to that of the device” require consultation by the Notified Body of the relevant Medicinal Products Authority (National Competent Authority or EMA), to seek their Scientific Opinion. This consultation process should be taken into account when planning the CE marking of such products or when planning a significant change to an already CE-marked product, as it greatly impacts the timelines for completion of the conformity assessment procedure.

United States

In the US, as a general rule, FDA requires a single application to streamline regulatory interactions with the Agency and the marketing application type generally coincides with the PMOA of the combination product. Hence for a device-led combination product, a single application should be submitted to the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) which acts as “lead center”.

A Premarket Approval (PMA) is required for class III device-led combination products; a De Novo Classification Request applies for novel device-led combination products for which general controls alone, or general and special controls, provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the intended use (class I and class II); a Premarket Notification (510(k)) applies when the substantial equivalence of the device-led combination product can be demonstrated against a predicate product.

Of note that, as part of the single application, sufficient information should be provided on the drug constituent part and may include nonclinical pharmacology, toxicology and clinical pharmacology (including pharmacokinetic) data and chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) information.

Combination Products regulated as drugs

Both in the EU and in the US, combination products with a drug PMOA, also called drug-led combination products, are regulated as drugs.

European Union

In the EU, “Devices incorporating a medicinal substance as an integral part which has an action principal to that of the device” and “devices intended to administer a medicinal product, placed on the market as a single integral product” are regulated as medicinal products under Directive 2001/83/EC or Regulation (EC) No 726/2004, as applicable.

In this context, Article 117 of the MDR introduces an amendment to Directive 2001/83/EC, requiring that the Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) includes the results of the assessment of the conformity of the device part with the relevant General Safety and Performance Requirements (GSPRs) set out in Annex I of the MDR. This translates into two cases:

- if the device part classifies as a class I medical device, then the evidence of conformity to the relevant GSPRs is provided as part of the manufacturer's EU Declaration of Conformity;

- if the device part classifies in any other way (i.e. class Im, class Is, class Ir, class IIa, class IIb, and class III), then the evidence of conformity to the relevant GSPRs is provided either as the CE certificate issued by a Notified Body (if the device is CE marked), or as the so-called Notified Body Opinion. In the latter case, careful planning of the submission of the Technical Documentation of the device part to the Notified Body must be done to ensure sufficient time for review by the Notified Body and obtain the Notified Body Opinion, to be included as part of the MAA.

United States

In the US, for a drug-led combination product, a single application should be submitted to the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) which, acts as “lead center”.

For a new drug-led combination product, the single application is a New Drug Application (NDA); for drug-led combination products that are the generic version of already-approved drug-led combination products, the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) is, in general, the most appropriate pathway. It's worth noting that the ANDA is based on providing sufficient information to demonstrate that the proposed product is bioequivalent to the Reference Listed Drug (RLD). To do so, the ANDA of a drug-led combination product should also include sufficient information to demonstrate that the device constituent part is compatible for use with the final formulation of the drug constituent part.

At Medidee, now part of Veranex, we have a long track record of providing expertise and technical knowledge to the Medical Device industry. Our Regulatory, Clinical and Quality support for combination products covers all product development stages, to the particular benefit of Pharma companies developing drug-delivery combination products, who may lack a medical device-oriented vision of the regulatory framework.

If this is something you are currently working on, do not hesitate to check our full offering of Combination Products Services, or to reach out directly for expert support.

This article was written by Rima Padovani (PhD, RAC) and Bruno Strappa (MSc).

[WEBINAR] Introduction to ISO/IEC 27001 – Information Security Management Systems

Introduction to ISO/IEC 27001 – Information Security Management Systems

Information security is a critical field dedicated to safeguarding an organization's digital assets, data, and information systems from unauthorized access, breaches, theft, or damage. In an increasingly interconnected and data-driven world, information security is paramount, as the value and vulnerability of data continue to grow.

Current challenges related to information security, include:

In this recorded webinar, Somashekara Koushik Ayalasomayajula, Kim Rochat and Cédric Razaname from Veranex provide you with:

- A foundational understanding of ISO 27001, its purpose and its significance in information security management.

- An understanding of how ISO 27001 helps organizations meet legal and regulatory requirements related to data protection.

- The core concepts and principles underpinning ISO 27001, such as risk management, information security controls and continual improvement.

WATCH THE WEBINAR

Please submit the form to watch:

[WEBINAR] Regulatory Strategy for New Neurological Medical Devices

Regulatory Strategy for New Neurological Medical Devices

Regulatory considerations and preclinical aspects are major parts of getting any medical device to market. Finding an efficient and cost-effective strategy is particularly challenging when the device in question:

In this recorded webinar, Dr. Olivier Chevènement and Dr. Richard Curno from Veranex provide you with:

WATCH THE WEBINAR

Please submit the form to watch: